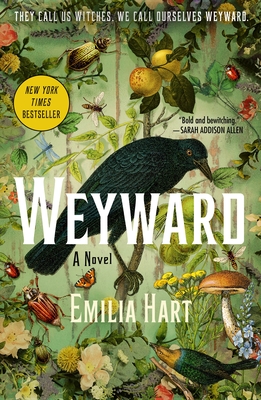

Summary

I am a Weyward, and wild inside.

2019: Under cover of darkness, Kate flees London for ramshackle Weyward Cottage, inherited from a great aunt she barely remembers. With its tumbling ivy and overgrown garden, the cottage is worlds away from the abusive partner who tormented Kate. But she begins to suspect that her great aunt had a secret. One that lurks in the bones of the cottage, hidden ever since the witch-hunts of the 17th century.

1619: Altha is awaiting trial for the murder of a local farmer who was stampeded to death by his herd. As a girl, Altha’s mother taught her their magic, a kind not rooted in spell casting but in a deep knowledge of the natural world. But unusual women have always been deemed dangerous, and as the evidence for witchcraft is set out against Altha, she knows it will take all of her powers to maintain her freedom.

1942: As World War II rages, Violet is trapped in her family’s grand, crumbling estate. Straitjacketed by societal convention, she longs for the robust education her brother receives––and for her mother, long deceased, who was rumored to have gone mad before her death. The only traces Violet has of her are a locket bearing the initial W and the word weyward scratched into the baseboard of her bedroom.

Weaving together the stories of three extraordinary women across five centuries, Emilia Hart’s Weyward is an enthralling novel of female resilience and the transformative power of the natural world.

Review

ReviewThe first thing I have in my notes for this book is that SO many of the negative reviews I’ve seen are basically just about how we as a society shouldn’t be focusing on books about violence against women anymore because that’s problematic and we are sooooo over it. That’s right, ladies! Ignore it and it goes away! There is nothing insultingly oversimplistic about the idea that it’s inherently exploitative or sexist to write about violence against women! It’s certainly not a vast issue that impacts us almost universally, and art shouldn’t reflect the full diversity of human experiences, including those that are traumatic and life-altering and uncomfortable to read about ! This violence is not widely misunderstood and stigmatized and ignored, requiring broader visibility, discussion, and understanding to be addressed in the real world! Survivor voices don’t already get shamed and suppressed when we try to speak about it!

Okay so obviously this is an argument I disagree with. One of the main reasons I decided to embark on my Trauma in SFF reading project is that I find critiques like this to be so frustratingly limited; my thoughts about violence against women in fiction are much more about what different books choose to ***do*** with that violence than simply whether or not it exists, and I wanted to try to contribute to that deeper conversation. I think Weyward is actually a pretty good example of why I find that level of analysis to be meaningful.

This isn’t a book that I find deeply troubling or angering in how it talks about abuse and sexual assault (except for one thing that I’ll mention later). It’s attempting to explore the pain and injustice of these things and the process of overcoming them. I actually just found everything about it to be really, really predictable and surface level. By the end of each character’s first POV chapter I anticipated exactly how the beats of her story were going to play out, and I was right about everything except the finest of small details. None of the women ever felt like true, distinct characters to me, and I didn’t find any of their experiences with sexism and violence to be particularly nuanced, powerful or thought-provoking in how they were explored. It was all just……fine.

A few specific thoughts that I wanted to mention…I’d seen some reviews describe this book as pro-life, which I’m not really sure about. One reason for this interpretation is that Kate debates termination but ultimately decides to have the baby conceived with her rapist/abuser; however, none of this is couched in anti-choice language/tropes, and it is a perfectly valid decision that many women make. The other thing is that Altha (the POV character from the 1600s) reflects that providing her abused friend with an abortifacient would be a sin. This is the sketchiest thing to me, particularly because Altha and her mother have deliberately eschewed all other tenets of Christianity and only go to church to avoid getting in trouble. So why does Altha think of abortion as a sin, Emilia?????

Next, the book’s one Feminist Statement that really fucking annoyed me: after Kate has used her newfound witch powers to sic a swarm of birds on her abuser, someone asks if she should still be concerned about him being a danger to her and the baby. She reflects:

“[He was] powerless, once she had robbed him of his only weapon: her fear.

‘No, he can’t hurt me anymore.’”

Okay lol. I get that the Empowering Sentiment here is that freeing yourself from your abuser’s mental control is a huge step towards escape and independence. That’s definitely true, and no longer living in fear is a part of healing for many people…but the way this is phrased extends beyond that to implying that this guy’s ONLY weapon against Kate is her perception of him as dangerous and now that she’s left him and is not afraid of him anymore, she has nothing to worry about. That’s just, like, not the truth of danger and harm in domestic violence situations at all?? Many abusers remain incredibly dangerous whether or not the survivor continues to perceive them as such -and if they do see them as dangerous, they learned to do so for reasons that make continued caution extremely reasonable and necessary.

This kind of take on empowerment (which is frustratingly common) wraps around to being really insulting to survivors in its implication that Not Being Afraid Anymore is a conscious choice that you can and should make in order to free yourself from your abuser’s shackles of control instead of a being complicated healing process that usually involves distance, time and the actual lived experience of safety. The unspoken (and likely unintended) messages are that 1) if you’re still afraid of him, you’re enabling his continued abuse and you’re therefore still responsible for shaping the actions of the man harming you and 2) continued vigilance is not an important thing to consider post-separation. Idk if those are things you want to be implying in your Daughters of the Witches They Couldn’t Burn book but what do I know?

Leave a comment