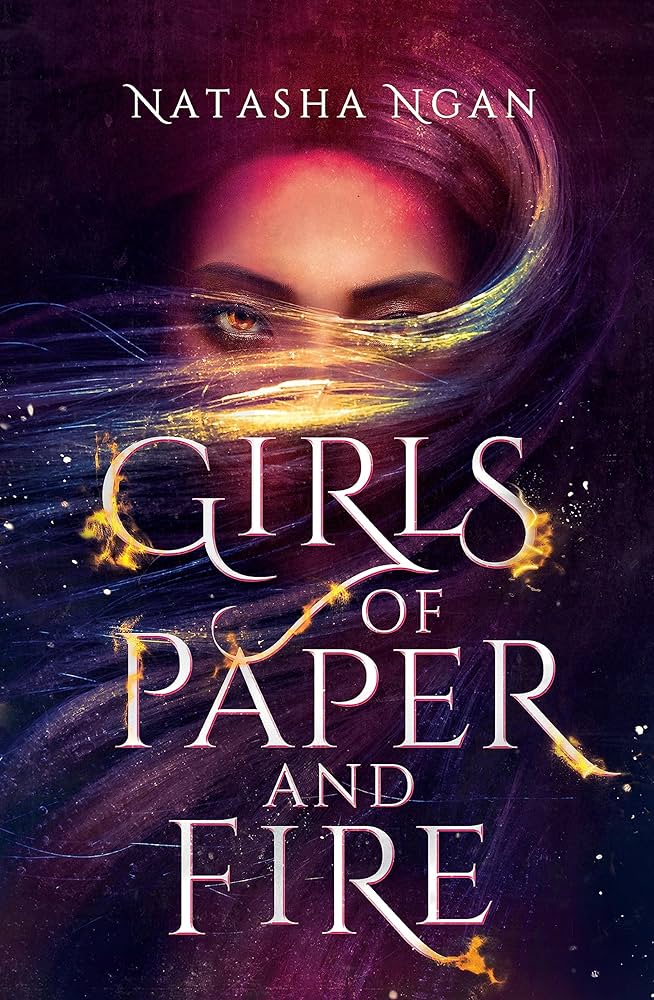

“When the world denies you choices, you make your own.”

Year published: 2018

Categories: YA, fantasy

LGBTQIA representation: F/F, main character, her love interest and side characters

Summary: in this richly developed fantasy, Lei is a member of the Paper caste, the lowest and most persecuted class of people in Ikhara. She lives in a remote village with her father, where the decade-old trauma of watching her mother snatched by royal guards for an unknown fate still haunts her. Now, the guards are back and this time it’s Lei they’re after — the girl with the golden eyes whose rumored beauty has piqued the king’s interest.

Over weeks of training in the opulent but oppressive palace, Lei and eight other girls learns the skills and charm that befit a king’s consort. There, she does the unthinkable — she falls in love. Her forbidden romance becomes enmeshed with an explosive plot that threatens her world’s entire way of life. Lei, still the wide-eyed country girl at heart, must decide how far she’s willing to go for justice and revenge.

My Thoughts: in many ways, Girls of Paper and Fire feels like the YA-est YA I’ve read in a while – there’s a beautiful protagonist with special eyes who doesn’t know how beautiful she is and randomly walks into things because the most loveable character flaw is clumsiness; there’s the pseudo-dystopian world-building with somewhat vaguely defined castes and class oppression and magic; there’s a romance that feels a lot like instalove; there’s that first-person present tense writing style that basically every best-selling YA fantasy author seems to adopt effortlessly. And yet I think it would be cruel to entirely dismiss it on those grounds, because, at the same time, this book is one that earnestly deals with the topics of sexism and sexual assault. I feel that it deserves a serious look at how it does so.

I think that the book’s biggest strengths and weaknesses lie in the relationships between the titular girls of paper and fire. One one hand, we get to see how different people react to situations of entrapment and sexual violence differently – Aoki falls in love with the Demon King in a rather trauma bond-y kind of way; Wren retreats into herself; Lei has conflicting feelings that confuse and disturb her – while she feels ashamed that she is chosen to be the King’s consort last, another part of her hates that she feels that shame and desire to be chosen.

How they are treated as a group is also interesting. Paper caste slaves hate them and more elite castes think that they’re whores. We see the way that women are complicit in violence against other women with their teachers and the book talks about how resistance can take many forms when you are stripped of choices in Lei’s conversations with the older consort Zelle.

At the same time, the girls are very hastily sketched characters with the exception of Lei and Wren. At one point Wren talks about how they have become something of a family to her but this just doesn’t ring true at all, especially when the majority of them have never been fleshed out beyond a single characteristic: mean girl, mean girl’s sidekick, religious, twins, main character’s BFF. Wren herself is probably the most interesting character in the story, but the relationship between her and Lei is, as mentioned before, pretty much YA-brand instalove (at least in my opinion). I really love the fact that their relationship is their way of reclaiming their bodies and emotions, and I love the scene where Wren shows her a hidden tree with lost/killed women’s names on it, but those are the only things that really stand out.

There is one bit of the story that bugged me: multiple characters tell Wren that she has more “integrity” and “fight” than the other girls because she tries to fight the Demon King when he first tries to rape her. As far as I know from my education in psychology, my own therapy and my work, when we are faced with overwhelming danger the prefrontal cortex (part of the brain responsible for advanced thinking/planning and higher functioning) shuts down and the sympathetic nervous system and mammalian brain take over to activate a crisis response, be it fighting, fleeing, freezing or fawning. Your response to trauma in the moment of danger is not a measure of character strength; it is simply an automatic survival response. It bothers me that it is treated as anything else, especially a way to make Lei seem better than the other girls, and especially when many of the sexual assault survivors I work with feel a tremendous amount of shame or like their assaults don’t “count” because they simply froze in the moment and did not fight back.

In moments where Lei does make deliberate decisions, some of them are frustrating. When she decides to speak up about the Demon King and his injustices, we are supposed to see it as her being brave and strong, and to a certain extent I do understand that. On the other hand, I think you could also see her actions as extremely rash ones that ultimately do more harm than good – for example, she reveals to the King that there is a rebellion against him when he previously just thought that she was “betraying” him with Wren, and this ends up completely derailing the rebels’ plans. The aforementioned mean girl Blue does have one moment of greater complexity when she makes it clear that she has no choice in doing what the Demon King wants and can’t speak up/fight back the way Wren does, and I like that the author made that point.

While I did have these problems with the book, I still think that it did other things well and could be a really good gateway book into difficult topics for young readers. And as I mentioned in my review of The Mirror Season, it also means a tremendous amount that this is a story about resilience and empowerment written by a survivor – I think that is always an amazing thing.

Leave a comment